Enter label: the Healing Secrets buried with a Neanderthal 100,000 Years Ago

Why the origins of reverence matter to nervous system healing practices

Dear Companions,

In the last post, we journeyed to the ancient healing world of Apollo in 500 BCE. Today, let’s go decidedly further—100,000 years back. Evidence suggests that burial practices may have begun during this distant past. The reasons for these practices remain debated, and the dispute will likely continue, but for me, the implication of reverence is enough to inspire my fight in the Healingvrse. Here’s why.

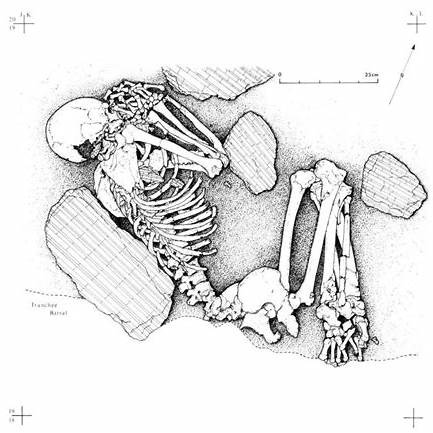

In the 1960s, French archaeologist Ralph Solecki excavated Shanidar Cave in Iraq and uncovered a Neanderthal burial (Shanidar IV) surrounded by clusters of pollen from flowering plants. These flowers, identified as having medicinal or aromatic properties, raised profound questions.

Were these flowers intentionally placed as a sign of respect for the dead—a ritual, an ancient form of love? Or, as some researchers argue, was the pollen introduced later by burrowing rodents or bees? Another possibility lies somewhere in between: the structured covering of the body may have been driven by a self-preserving instinct—to protect the living from predators like early vultures—while still reflecting care, protection, and love. Regardless of the exact motivation, these acts demonstrate a depth of connection that shaped the survival of our species. It shows that they were engaged in behaviors that revered the dead, symbolic thinking, and humanity.

The time of these people, that skeleton found, is so long ago, that it is almost impossible to fathom now—like imagining how one might live on Mars—and yet, this information, this idea of information, supported by the faintest brush of an archeologists tool, can make me feel so connected to that person, whose gender is yet unknown, I practically weep for her death, and too, attend her burial over and over in my mind.

Why This Matters in the Healingvrse

Why do these questions capture the imagination of someone in the Healingvrse? Why do they fascinate us amidst our modern struggles and lingering fears of mortality?

For me, it’s this: the instinct for empathy, respect, and love is so deeply hardwired that it rivals our appreciation of fire. Widespread use of fire began about 400,000 years ago, revolutionizing human evolution by supporting the development of larger brains and smaller guts—no longer needed to digest bulky herbivore diets. And yet, these advanced brains weren’t only used for survival. They were used to create moments of ritual, reverence, and love—wordless ceremonies like placing branches over a loved one’s body under a star-filled sky, with the calls of mastodons and saber-toothed cats in the background.

This suggests that, deep within our limbic system—the part of the brain that layers emotion and meaning onto the primal, autonomic functions governed by the brainstem—lies a hardwired desire to connect, to show gratitude, to honor life. We often discuss the amygdala and hippocampus in terms of balancing the autonomic nervous system, but how often do we consider how they process emotions like awe, gratitude, and reverence? These emotions aren’t luxuries; they are foundational to our humanity, as ancient as the first spark of fire.

For someone like me, navigating recovery, these old facts have become oddly comforting. They elevate the practice of mind-body regulation by reminding me how sacred this system is. To think that, even in our earliest days, humans found ways to honor life and love—it adds a new dimension to the feeling that I am not alone.

Sometimes I wonder now too—did they get headaches? Were they plagued by stress? Aging?

How does this type of info make you feel? Does it inspire you, or do you feel completely disconnected from it? I’d be curious to hear your thoughts.

Some sources to enjoy

If you’re curious about this research, and the habits of Neanderthals generally, including how early Homosapiens likely reacted to this dying species, you can explore it further in the Netflix series Secrets of Neanderthals.

Other burial sites to check out:

Qafzeh and Skhul Caves (Israel): These sites contain remains of early modern humans (Homo sapiens) buried with grave goods, dated to about 100,000 years ago.

La Ferrassie (France): Neanderthal remains from about 70,000 years ago suggest intentional burial practices.

A slight tangent, and far more recent (2000 BC), but still fascinating talk on ancient ritual practices, ancient astronomy, and mathematic in Mayan civilization.

With much love from the Healingvrse,

Rebecca